Mastering the Art of Pacing: How to Keep Readers Hooked from Start to Finish

Budding writers may ask: why is pacing important? There are reasons aplenty. For one, and probably most importantly, to keep the readers engaged, and this is true irrespective of the genre. Another important aspect is to keep the reader guessing after drawing them into the story in the first place, wanting to know what comes next, and adding to the thrill of reading. Entertaining the reader, responding to the senses you wish to inflame, can surge, wane, or diminish, all depending on pacing, irrespective of the plot. It’s an essential element of writing. An interesting twist to this facet of writing is that genre does have an impact on pacing, and I will explain why. I have also included a few helpful tricks and tips from my personal experience writing as well as reading successful works of fiction.

So, what is pacing?

Before we delve deeper, let’s establish a few fundamentals. What exactly is pacing? Is it the speed at which the plot unfolds, revealing facts and information to the reader? Is it depicted by frenzied action interspersed with periods of reflection or less action? Does sentence structure matter? What about dialogues – if your plot is conversation-intensive, is it still possible to maintain the right level of pacing? The answer to all the above is a resounding yes, and again, irrespective of genre. Oh, except perhaps the “frenzied” part of action – that may apply only to certain genres, like thrillers.

Examples of Effective Pacing in Fiction

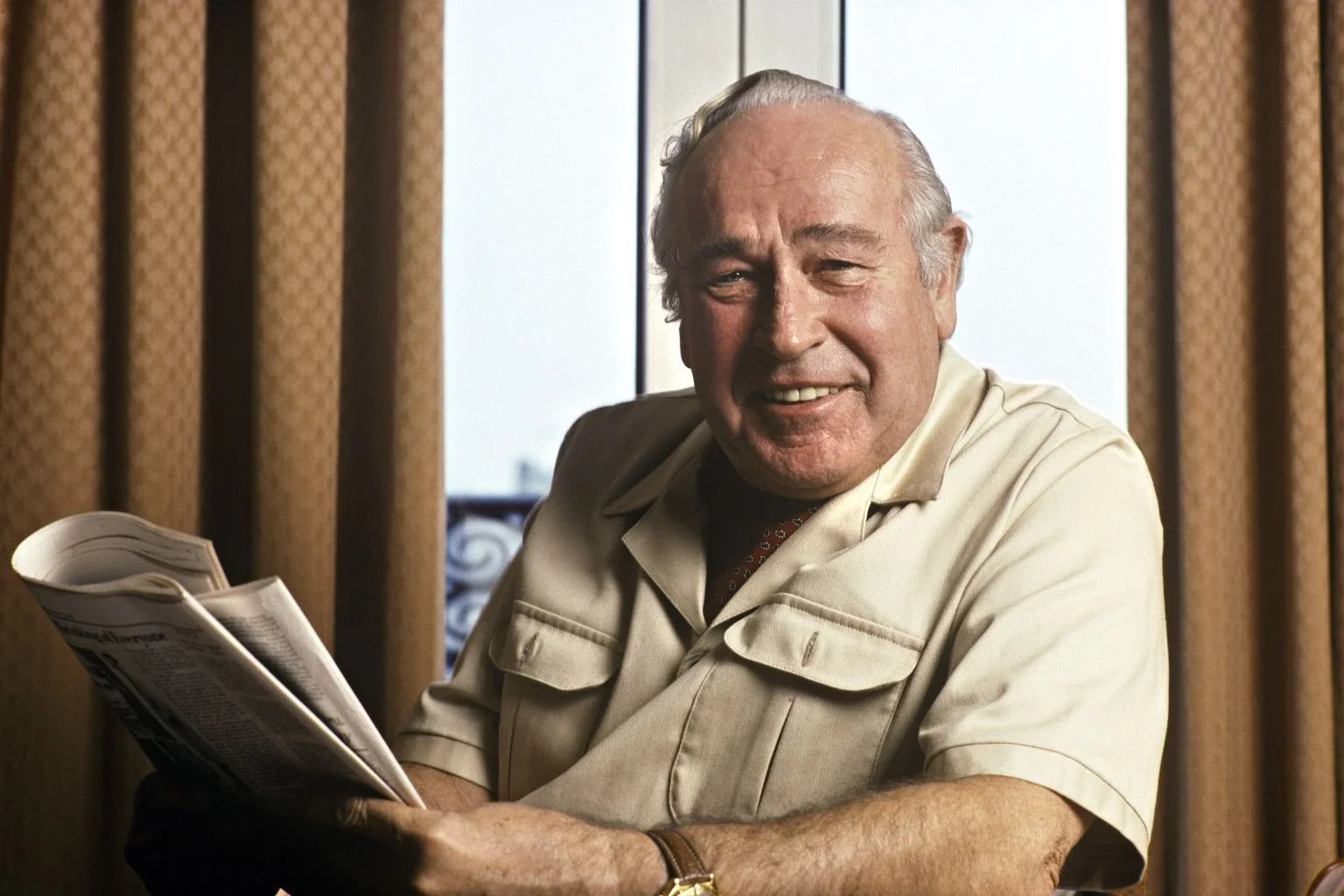

Robert Ludlum - best known for the Bourne Trilogy

So, what are some good examples of pacing? Robert Ludlum is one of my favourite authors for fast-paced, frenetic, almost non-stop action right from the get-go. Yes, there were quieter periods that only served to emphasise the pace and allow the reader to catch their breath. To answer your unspoken question – yes, absolutely essential, and also to allow for reflection, explanations, clues to the reader, and so forth.

Ian Fleming, Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, Agatha Christie, David Baldacci, Mary Higgins Clark, Michael Crichton, Jeffrey Archer, Ruth Rendell, Danielle Steele, Irving Wallace, J.K. Rowling, and Dan Brown are other examples of authors who delivered thrillers that quickened the pulse and took the readers’ breath away. Mary Higgins Clark was noteworthy in how, juggling between multiple perspectives, she was razor-sharp in pacing. Had to be.

The Impact of Genre on Pacing

Finally, before we get to the meaty part, one more point to note: while pacing is equally important, it does differ from genre to genre. We’ve already spoken about thrillers. Romance, especially category romance, has its own ebbs and flows with a reasonable amount of pace but not the Usain Bolt speed. Here, action and events are more about how the drama unfolds between the leads.

Pacing is essential in all genres, but the way it’s handled can differ significantly depending on the type of story being told. The key reason for this is that each genre comes with its own set of reader expectations.

“A fast-paced romance might feel rushed, just as a slow-paced thriller might fail to deliver the necessary tension.”

For example, in thrillers, readers anticipate a fast-paced narrative filled with tension, surprises, and high stakes. This genre often uses shorter sentences, quick scene transitions, and cliffhangers to keep the reader on the edge of their seat. The relentless pace helps to maintain a sense of urgency and suspense, which is central to the reader's experience.

Romance, on the other hand, usually requires a more measured pace. While there can still be moments of high tension, the focus is often on the emotional journey between characters. This means more time is spent on dialogue, character introspection, and the development of relationships. Here, pacing may slow down to allow readers to fully engage with the characters' emotions and the evolving dynamics of their relationships.

Long, sprawling epics like Boris Pasternak’s Dr Zhivago or Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind are examples where pacing is intentionally slower to accommodate detailed world-building, complex character arcs, and expansive plots that unfold over a long period of time. These stories ebb and flow, with bursts of action interspersed with long periods of reflection or description.

In literary fiction, where the focus is often on language, themes, and character development rather than plot, the pacing can be even more variable. Here, the reader is more likely to tolerate (and even expect) slower, more contemplative pacing.

The influence of genre on pacing is ultimately about meeting the expectations of the reader. A fast-paced romance might feel rushed, just as a slow-paced thriller might fail to deliver the necessary tension. Understanding the pacing norms within your chosen genre is key to creating a satisfying and engaging story.

Spotting and Fixing Poor Pacing

Easy to spot

It’s relatively easy to spot examples of poor pacing, although opinions may vary depending on interest.

It’s relatively easy to spot examples of poor pacing, although opinions may vary depending on interest. But setting aside those who only prefer thrillers to the exclusion of all other genres, the biggest clue is – losing interest in the story and putting the book down. Another, less extreme clue is skimming the pages, equivalent to fast-forwarding boring scenes in a movie or television show. The best compliment I have ever received from a reviewer is a single word – unputdownable!

Harder to fix, I imagine, but we will cover, towards the end, a few writing exercises that will help and what not to do, and why. More precisely, how the modern writer can also – erm – cheat but mustn’t. The best way to spot pacing in your own writing is to … roll of drums, please … read it! Not like you’re checking for errors but as though you are enjoying someone else’s work. If you are genuinely enthralled, then great. If you find yourself drifting off, skimming, or deciding to continue later after a cuppa, then that’s a huge clue that something’s wrong.

Tips for Improving Pacing in Your Writing

Start Strong

The first few pages of the book should draw the reader into the story and give the basis for where it’s going, even if it’s a suspense or a thriller. Don’t get me wrong. World-building is important but who says this needs to be booooring? Another tip – avoid simply giving the reader information, rather show them through a scene or dialogue, but keep it short and impactful.

Vary Sentence Length and Structure

Short, punchy sentences speed up the pace, and longer sentences slow it down, but a good balance between longer and shorter sentences keeps the reader engaged. Having said that, the trick is not to have too long a sentence, where the reader has to go back to the beginning to give it a once-over in order to get the point. Two-word or single-word sentences in between longer ones tend to retain attention.

Control the Release of Information

The most beautiful thing about writing, as opposed to making a movie, is – words on page allow the reader to imagine. Just the right amount of description is needed, but too much information can spoil this for the reader. The right balance will build an image for the reader, while still allowing their imagination to fill gaps. To maintain the right level of pacing, allow for drips of facts and tidbits through the plot to keep them guessing and turning the page to find out what happens next.

Use Scene Breaks and Chapter Endings Effectively

I simply love cliffhangers as a way to keep readers wrapped up in the story, but there are a few points to note before using them. Section breaks are great to allow the readers to pause, reflect, grab a cup of tea, or simply go back to work (Lol!). They need to be evenly spread, unless a very short section is required for impact – more useful in a thriller where you want to draw the reader’s attention to an important event.

They can occur when a perspective changes, or when a scene ends, indicating a time lapse, change of locale, or the ending of a conversation. Remember how important it is to retain interest while the reader takes a break? Introduction of a new piece of information or raising a question is useful, but let’s not confuse this with a cliffhanger. The latter should be sparingly used, typically at the end of a chapter that makes the reader go – what’s gonna happen next? In fact, I tend to factor cliffhangers in the very first draft plot so it never escapes my attention.

Balance Action with Reflection

Easier to achieve in thrillers, the plot will naturally allow for periods of relative inaction, where both the characters and readers can take a breath. Ludlum was probably the very best at not just commencing the story with frenzied action but sustaining the pace throughout, except for those brief moments where the pace slowed down and allowed the character to recharge.

In romances, to give another example, where dialogues between the leads and events befalling them help sustain the pace, inner monologue tends to slow it down. Again, balance is important. Another important point is – no matter the genre, too long a dialogue or quieter inner reflections can tend to lose the reader’s interest. In simpler terms, pacing is not just about feverish events cascading together, action upon action sequence, but a healthy mix of both.

Eliminate Unnecessary Details

I’ve already mentioned the danger of providing too much detail that can a) bore the reader as they are not interested, b) prevent the active use of their imagination to fill in the blanks, or worst of all, c) give them too early a resolution, so they put the book away. A re-read of your manuscript will allow you to spot these quite easily. Or you can get a beta reviewer to do it for you.

Also note that the characters need to develop, change, and grow through the course of the narrative as the reader gets to know them better. Too many details mean more opportunities for error, making copyediting a big challenge.

Writing Exercises to Improve Pacing

Now for some writing exercises, in no particular order of priority, to help with pacing:

Word Count Reduction: When writing a sequence, like, for instance, an action scene, experiment with the number of words consumed by the sequence. If your original version had, say, two hundred words, try writing the same sequence in half, then halve it again. Or simply go to the extreme and write it in twenty words. Cheat sheet: Modern AI will do it for you, but that’s just being lazy and defeats the purpose of the exercise. The benefit of shortening longish sequences is retaining attention, as a reader may get distracted if the scene goes on forever.

Monitor Inner Monologue Length: Monitor the length of inner monologue, quiet reflection, inaction, or slower-paced scenes against the other kind. Tip: They shouldn’t be equal, as in this instance, the right balance doesn’t mean the same length. If necessary, perform the first writing exercise to reduce it and make it more impactful. The key is – what are you trying to convey to the reader by this sequence? Can it be achieved with fewer words?

Experiment with Cliffhangers: This one is more for the drafting stage but works equally well while editing. Can you break a particular scene in the middle of the action? Or when a question is left hanging? Perhaps you can make a few small changes to the scene to allow for it? Always try to end a chapter with an open question, preferably a life-changing one for the characters. In the final version of my manuscript, I ensure each chapter ends with a mini cliffhanger, so it doesn’t matter how busy the reader is, they just have to know what happens next.

Read Aloud: This is one of the best ways to check the pacing in your writing. If the flow feels off when you read it out loud, it probably needs revision. You’ll be able to hear the rhythm of your sentences and catch any awkward or slow spots that might disrupt the pacing.

Pacing is, without doubt, one of the most important elements of writing, which, if done right, will keep your readers coming back for more. A good grasp of the concept, applied equally well in every scene, will make a world of difference to the book's quality and readability. As with every other element, practice is key to improving pacing, and soon you’ll be crafting unputdownable stories that resonate with readers long after they’ve turned the last page.

I try. I don’t always succeed. You see, it’s the journey. It has to mean something. It has been for me thus far, and I have hopes for the future. Hope you’re with me. Let me know what you think.

Mark Ravine

If you enjoyed this, you may like: